Newspapers told the world of an Illminster harvest one hundred and seventy years ago.

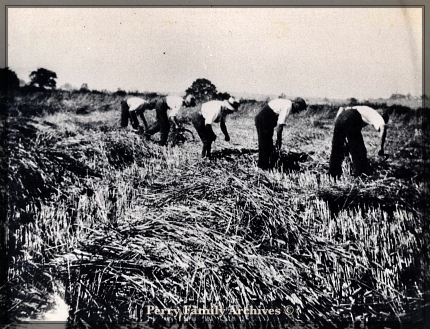

- A harvest that became a public event for ten brothers.

- Mullins family made national newspapers while reaping of a wheat field at Cross, Ilminster.

- Town folk turn out to watch the father and his sons, ten fine grown men reaping the crop of wheat.

In August 1850, in the season of gathering foods from the land, dozens of national newspapers carried a story originating in a field near Ditton Street, Ilminster. It portrayed a father and his ten sons reaping a field of wheat.

‘Ilminster – Reaping Extraordinary.

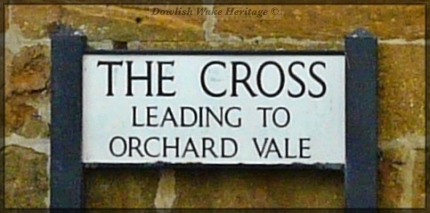

On Saturday, in a wheat field, situate near the Cross Gate, adjacent to the town, were to be seen a father and his ten sons reaping. The field is rented by one of the sons and by his request, his father and his brothers helped to reap his field of wheat. The father is an athletic

This appeared in the edition dated; Tuesday 27th August 1850 of The Western Flying Post, Sherborne and Yeovil Mercury, as printed.

The end of August came, and the day arrived. The workforce had been recruited, their implements sharpened; sickle, reaping or bagging hook, all used in Somerset at this time. Consideration given to weather the crop is ready to be cut by hand.

The men lined up in their reaping attire, linen smock or collarless shirt plus a hat bedecked with carnations. We know of this head attire from recalling the reaping party from its telling in the book; The Mynster of the Ile published 1904. The interview of that year with Noah Mullins, one of the brothers, reveals;

‘Men used to be so joyful in the harvest work then – whether reaping or mowing – they went forth as to a holiday, always with carnations in their hats and worked as men who loved it’.

We presume these men no strangers to the hard labour in front of them. Backbreaking work, stooping and bending, the reaping action requiring an agile body and a great deal of strength. Each knew the pecking order, their place on the field determined by their skill and speed, governing whether, or not, a fellow would be in danger of a blade just too close to his heels.

What a sight it must have been, the 11 men in a staggered row, several feet behind each other, swinging their blades, supple body needed to reach the base of the stems, heavy hot work. Easy to imagine the competitive nature between these brothers as they got underway with humour and teasing. Knowing too, that many in the crowd watching would be judging their progress. The description of that day in the national newspapers suggests how they presented themselves and were observed by the crowd.

‘The father is an athletic man named William Mullins aged 65 years’. The sons ‘Fine robust men,

A good description of the motion needed is given in E.J.T Collins work ‘Harvest Technology and Labour Supply in Britain 1790-1870’. Page 243.

‘The art of hand-reaping is easily acquired once the initial tedium and physical inconvenience of the operation had been overcome. The usual mode is to crouch down on the right leg, clutch a handful of straw in the left hand, and draw the tool inwards in a cutting or sawing action, as near to and as parallel with the ground as possible. The reaper crept forward into the standing corn, laying handfuls of cut corn onto a ready-prepared band until enough had accumulated to form a sheaf. The sheaf would then be tied up, either by the reaper or his assistant’.

In the same publication on page 245, Collins refers to the role of family members, wives, children and relatives assisting the reapers;

'the weakest making bands or collection of loose straw, the strongest tying up and making stooks'.

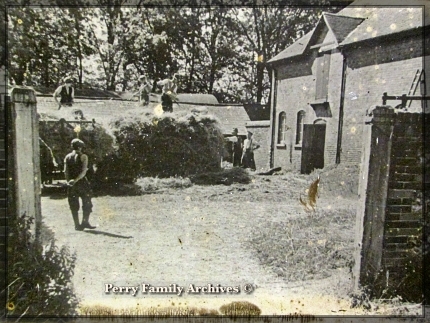

Bands were made of two handfuls of stalks, 2 ends twisted together, this laid on the ground, other stalks gathered up and tied in the middle with the band. This sheaf along with others then stood on end to form a self-supporting stook.

As the day progressed, they would have had to stop at intervals to re-sharpen their blades, judging the time needed for the task and still keeping up with each other. Stopping at times for refreshments, small beer, ciders, bread and cheese.

Come evening, the crop cut and neatly stood up and tied into stooks, allowing the grain to be free of the ground and benefit from the sun and wind to ripen. Later still, ‘harvest home’ all safely gathered in, stacked in the haystack or rick-yard, awaiting the threshing. Much merriment, usually a harvest supper with cider and ale, meats and pies, and puddings.

So, who were these 11 men and what of their background? The Mullin family, farmers and dairymen. Records place them at locations in and around Ilminster, Moolham and Axminster.

Father

William Mullins [63], of Pennsylvania farm, 90 acres, Axminister. [1787]

Sons

John [43], Farmer, New Park Farm, 120 acres Axminster. [1807]

William Jnr. [41]. Farmer 179 acres, Easthay Farm, Axminster. [1809]

Twins [38] [1812]

James, Agricultural labourer, Thorncombe.

Noah, Dairyman, Barrington.

Twins [35] [1815]

Esau, Dairyman, Eames Mill, Ilminster.

Jacob, Dairyman, Cross Gate, Ditton St, Ilminster.

Henry, [32] Wheelwright, Westwater, Axminster. [1818]

Matthew, [31] Dairyman, Ashwell, Winterhay & Moolham]. [1819]

Robert, [28] Agricultural Labourer, Pennsylvania farm. [1822]

Emmanuel, [23] Agricultural Labourer, Pennsylvania farm. [1827]

Source; 1851 census records and baptism records included here, as dates from this period often conflict. Likewise, the formal spelling of the surname Mullins/ Mullens.

Little is known of William’s wife, Rebecca [1785-1859] but most certainly a remarkable achievement to rear 13 or 14 children. They not only survived childhood but flourished at a time when infant mortality was high. The first set of twins was produced when Rebecca was 27, with already 3 children under 4 years old. These all thrived, and in 1815, the second set of twins was born. Other children followed, the last Emmanuel in 1827. Fourteen children are mentioned in the following newspaper report, but no details of the 14th are apparent.

We learn that William the father was walking an average of 15 to 20 miles a day by the end of his life, even up 6 weeks before his death. The Bridport News produced an excellent article at the time of William’s burial at Hawkchurch, aged 81. Living most of his life in Axminster, He the father of 14 children and the grandfather and great grandfather of 147 children. He had much respect for his children, visiting his offspring alternately, as fancy dictated.

Up and down the country, newspapers had carried the story of the "Reaping Extraordinary". Furthermore, some 55 years later, on the death of Noah Mullins in 1905, the Chard and Ilminster newspaper published this article.

‘Death of Mr Noah Mullins.

The oldest parishioner of Ilminster passed away on Wednesday morning in the person of Mr Noah Mullins, who had he lived until the 24th of the present month would have reached the great age of 94. Deceased, who was born at Hawkchurch, Devon, lived for the past forty years at Winterhay. His wife predeceased him some ten years since, and he is to be buried adjoining her grave at Hawkchurch, Devon, on Monday next. He leaves a son and daughter to mourn his loss, whilst there are also living 21 grandchildren and 25 great-grandchildren. He was the only surviving son of the late Mr William Mullins of Hawkchurch.

His death recalls an extraordinary incident, probably without parallel in the agricultural world. When reaping a field at Cross-gate, Ilminster in 1850, the deceased assisted his father and nine

The following are the extracts taken from one Important paper, ' A Family reaping party – On Saturday in a wheat field situated near the Cross gate adjacent to the town of Ilminster were to be seen a father and ten sons reaping. The father is an athletic man named William Mullins. His sons’ names and ages are John 40, William 38, Noah and James [twins] 36, Esau and Jacob 34, Henry 30, Robert 28, Matthew 32, Emmanuel 22 years. The sons are all fine, robust men, and on average, stand 5 feet 11 inches. A great many persons went from the town to see them reap, and the bells of the venerable church rang peals on the occasion.'

Right up to the time of his death, he retained all his faculties and was last season on numerous occasions working in his garden and taking a keen interest in his surroundings. His memory was very retentive, and he could converse on many important historical events that have taken place during the last 80 years. He was not an abstainer, and would often take of the 'weed', but his very regular habits and healthy occupation in his long life doubtless the means of his attaining the great age above mentioned’.

This was printed in the edition dated; Saturday, Feb 18th, 1905, The Chard and Ilminster News. Page 5, Newspaper Archives - findmypast subscription website

Just why 170 years ago was this event of importance and reported in national newspapers.

Why did this story seem worthy of national interest? This story was recorded and copied many times into national

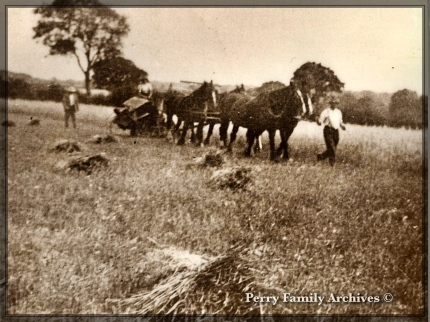

Perhaps it was concern that things could change, the old ways replaced by machines like the cloth weaving and spinning industry. Railways and Canals installed locally. The father and brothers must have noted the agricultural changes happening around them.Talk of the coming 1851 ‘Great Exhibition’ at Crystal Palace and Hyde Parks Royal Agricultural Society. Amongst the ‘new’ agricultural machinery and implements to be exhibited were reaping machines, Hussey’s and McCormick’s. Already steam engines were in production and to be seen on farms.

At local events, there were trials of the McCormick’s device for cutting grain crops. Drawn by two horses, attached to a pole, it travelled close to the right side of the corn.

Newspapers were full of reports such as:

‘McCormick’s American Reaping Machine’- ‘Even in its present form, it's likely to supersede the scythe, the sickle and the hook’.

“Nothing could surpass the beauty and regularity with which some standing corn was deposited by it, at its late trial, at the Royal Agricultural College at Cirencester. Taking the ordinary speed of a horse [say two miles and a half per hour] and recollecting that the machine being six feet broad, it will cut more than fifteen acres in a day of ten hours. It requires a man to take away the corn and a boy to drive the horses.”.

[Agricultural Gazette - September 20th.1851

At the same time, there was discussion of the merits of hand reaping by differing methods in newspaper archives. Hand reaping using either a sickle, reap hook, or the heavier bagging hook’, plus scythe mowing. Costs were an issue; a report in a Scottish newspaper indicates that the price of reaping or bagging wheat was 10 shillings an acre, including the beer! While cutting with a scythe, 7 shillings an acre, not including other manpower costs, raking and gathering. A report in the Bath Chronicle, page 7 in August 1845 of a trial at Maidstone resolved that;

‘It was found desirable to cut wheat before it becomes sickle-eared and other grain rather green. That if men can be got to bag wheat well, it is best to bag; the next best plan is to mow; but both bagging and mowing must be done well, or dirt will get into the sample, from the stalks, which are torn up by the roots’.

With all methods, the later threshing of the crop was also a factor in choosing whether to reap or mow; the secondary process of flailing or use of a steam threshing machine. The 1850 August edition of the Trewman's Exeter Flying Post discusses price, convenience, or method of reaping the crop. Choices

‘We saw a steam-engine of eight horse-power threshing mown wheat with straw about 7 feet long’.

Later in 1853, the Royal Agricultural college commented that “the sickle was the cleanest most expert and the scythe the most ‘slovenly’ tool. With hand reaping, perfect sheaves, well-placed stooks, shaven ricks and ornamental thatching! Whereas the scythe is thought of as ‘higgledy-piggledy’ work. [E.J.T. Collins, ‘Harvest Technology and Labour Supply in Britain 1790-1870’.

Decades before the reaping party in 1829, Reverend Patrick Bell of Carmyllie, Scotland, invented the horse-powered reaping machine, ‘propelled’ forward, not pulled. Mounted on a carriage with its 6 wheels, harnessed by two horses from behind, It was equipped with eleven pairs of open scissors. Claimed not only to cut the corn but with the use of 'an endless canvas web, revolving upon rollers it delivers the cut corn on either side of the machine, standing on its root end’. The cut grain in rows ready for binding into sheaves. Six hands following ‘quickly produce very neat tidy sheaves’. Requires two men and cuts twelve acres a day.

Yorkshire Gazette, 11th December 1852. & Dundee Courier 8th July 1986. & 26th September 1829, Edinburgh Evening Courant.

Machines were expensive, needed to adapt to different crops, field sizes, uneven ground, weather damage to crops, the length of the cut for efficient stooks, the type of cut achieved and stubble length. Hence, much thought going into the initial outlay expense.

Another factor to be considered, is that of agricultural labourers being enticed into cities and towns the decade before 1850. Also, there had been conflicts between agricultural workers and landlords following the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, concern and debate about harvests, markets, wages, prices and costings. From the tenant farmers point of view, he, needing the security of tenure and fair rent, favourable if his labour pleased his landlord. However, to be aware that making improvements to the land and stock, and so by improving yields, his rent could rise. All in all, harvest-time meant competing with other farms for a limited workforce.

Speculation continues as to why peals of bells were rung in Ilminster that day. Town folk gathered in a festive mood, watching this family, a father and ten brothers reaping. But it does introduce us to an era long gone but captured by James Street for his book, 'The Mynster of the Ile'. In which an interview was recorded with one of those brothers, Noah Mullins. Seemingly conducted at his farmhouse at Winterhay, Ilminster around 1904 before his death aged 93 in 1905. Speaking of Winterhay Green and its ancient beginning’s:

‘A parcel of the waste belonging to the manor: over which occupiers of manorial lands had unlimited right to de-pasture any number of cattle, at all times. On this Common at times were lively mobbing’s: the red flag was hoisted here, for instance, in the bread riots.

When Buonaparte was expected to land in England, on this Green the folk watched for the lighting of the fire on the Beacon Hill.

By an Act of the year of Waterloo, the Common was, with Hortmead, parted amongst those with rights and enclosed. Yet one of the most interesting houses on the Green survives, a Long low thatched farmhouse of – we suppose – Tudor times. The large open fireplace in the kitchen, the low windows, the heavy beams tell of ancient times. The home, this of the Rutter family; we seem to be able to trace back the occupiers, [through a mico], to a John Read, [in temp.] Charles 1.

But today the oldest person in Ilminster lives here. Fifty years ago, a London daily told the work of a certain field at Cross near Ilminster wherein a farmer

He tells that when he married over 60 years ago a shilling would buy a loaf of bread, a quart of cider, a pound of butter. A labourer’s earnings were then 1s.2d a day. Things had been much dearer, bread in 1811 was 16d, and they grew dearer again. So far, we live in better days’. But he tells us also, and it dwells much on his mind- perhaps the memory of the father and the ten sons in the harvest field bears upon it – “Men used to be so joyful in the harvest work then – whether reaping or mowing – they went forth as to a holiday: always with carnations in their hats, and worked as men who loved it”. The joy of harvest; dear old friend. May it be yours and ours, yonder!

Extract transcribed from the book published in South Africa - ‘The Mullins Family of Somerset’, October 1988 by Thomas Mitchell Mullins. In turn, having been transcribed from the book 'The Mynster of the Ile', Page 367

Descendants of the Mullins family are scattered far and wide, but earlier Mullins connections to Ilminster include:

Jacob at Cross Gate Dairy in Ilminster

Jacob at Rose Mills, Ilminster.

Mathew at Ashwell Farm, near the Cemetery Ilminster

Noah at Winterhay Farm, this farm was in ruins by 1985.

Their son William in 1870s & 1880s, innkeeper and farmer at the Slape Inn, Ilminster. [also known as Railway Hotel, Nelson Arms and later The Lord Nelson].

Esau and Emmanuel at Eames Mill.

John Coles in Ilminster, descendent of Matthew Mullins of Moolham Farm.

Connections to Dowlish Wake are;

Mathew Mullins and son William and families at Moolham Farm.

At Higher Dowlish Farm in the 1930s were Emma Hedditch Mullins and Hugh Samways Gale with

In the 1980s Alfie Gale and John Coles were instrumental in accompanying Thomas Mitchell Mullins to visit the various farms in the area where their Mullins ancestors had lived.

Two future articles are planned:

- Location of the Reaping Party and Turnpike House - Cross Gate, Ilminster

- The story of The Mullins Orphans

Our first knowledge of this family came from a two-page summary within the Dowlish Heritage files, entitled, ‘The Mullins Family At Moolham - The Orphans’. An overview of the sad story of the death of Noah Ellen Mullins in 1889, age 39, soon followed by husband William Mullins in 1891. [Both buried in St Andrews churchyard, Dowlish Wake]. Sadly, their five young children were consequently split up and scattered, all leaving Moolham Farm to live with different relatives. This story, sad that it is, is a compelling insight into local life at that time. A couple of years ago, we were also contacted by a descendant of this branch of the family, a great-grandson of the above, one Matt Mullins. He has been of great help, and we have exchanged much information. His father, Thomas Mitchell Mullins, published in South Africa the book; The Mullins Family of Somerset. During his research for the book, Thomas visited Dowlish Wake and Ilminster several times in the 1980s.

Sources & Notes

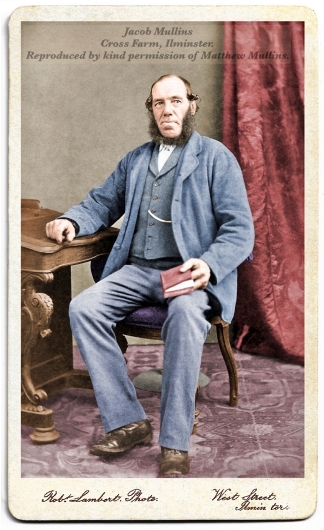

Jacob Mullins

The photograph of Jacob Mullins is reproduced with kind permission from Matthew Mullins.

John Symes Cuff – diary of 1858:

It's interesting to see that wheat crops grown in the 1850s were taller than present-day varieties. Locally, John Symes Cuff [diary of 1858], of Oxenford farm, mentions; Siberian, Kent and Nursery varieties. The original document is at the archive centre in Taunton. Catalogue no A/AGB/1. The entry reads [Wilsons] diary, possibly belonging to a farm in Chard/Ilminster area 1858.]

Ancestry.com online subscription website

1935 Kelly’s Directory

1939 England & Wales Register

Familysearch.org

Marriage of Rebecca Lane and William Mullins in 1806

thegenealogist.co.uk

BMD record of deaths, Rebecca Mullins, Axminster, 1859

Books

“The Mullins Family of Somerset’ published in South Africa, October 1988, by Thomas Mitchell Mullins

The Mynster of the Ile.

Noah Mullins Carnations on the hat. Printed on page 369, published in 1904, its reference is taken from the book; The Mullins Family of Somerset,

Newspaper Archives – findmypast.co.uk online subscription website

Ilminster – Reaping Extraordinary: Tuesday 27th August 1850, The Western Flying Post, Sherborne and Yeovil Mercury,

Hawkchurch Burial of William Mullins in 1868. Bridport News and Dorsetshire, Devonshire and Somerset Advertiser. Published Saturday 7th March 1868.

13 or 14 Children of William and Rebecca Mullins, a reference to 14 children in the article above; Hawkchurch burial of William in 1868.

Scottish newspaper prices for reaping. The Brechin Advertiser, and Angus and Mearns Intelligencer, 19th September 1854.

Reports of costs of harvesting wheat. Article Farmers Journal, ‘On Harvesting Wheat’, Trewmans Exeter Flying Post, August 8th, 1850. Page 6.

1853, the Royal Agricultural College. [Harvest Technology and Labour in Britain, 1790 – 1870, By EJ T Collins, May 1970. page 265, The Constraints on Hand-Tool Innovation, eprints.nottingham.ac.uk

1851 ‘Great Exhibition’ at Crystal Palace; Article in Wilts & Gloucestershire Standard and Cirencester and Swindon Express August 28th, 1852. Headline ‘Royal Agricultural College’.

The American Reaping Machine. [‘Agricultural Gazette’ - September 20th 1851. Printed in the Westmorland Gazette and Kendal Advertiser]

Books

Harvest Technology and Labour Supply in Britain 1790-1870. “The art of hand-reaping is easily acquired once the initial tedium ", etc.; EJT Collins’ work. Page 243. online - eprints.nottingham.ac.uk

An Account of the Farms and Farmers of the Parish of Axminster since the Agricultural Revolution. This is useful for further detail of Axminster members of the Mullins Family, for those interested in the farms in that area. The publication; By David J Knapman. November 2017. See online at website axminsterheritage.org

Countryfile Magazine – Explore the British Countryside – ‘The golden age of the harvest’. Online; countryfile.com

The descriptive name; ‘corn’, use interchangeable in the past for wheat and other grains.

Online views of reaping:

JakHickman @actonscottfarm – twitter - Acton Scott Near Church Stretton [video]

Cyrus McCorick’s Reaper: Changing Farming Forever by Lance McConkey – edubilla.com [video]

Wikimedia Commons – Illustration; File George Heriot Swanston03.jpg [Patrick Bell’s reaping machine 1851]